Comparing directories: a case study

The problem #

Let’s say we have a directory called O that contains a large number of subdirectories and files.

We find ourselves with two different directories, A and B. Each of them started as a copy of O, but then, in each of them, some files were changed, some were added or removed, and we don’t know which ones.

We want to compare the contents of A and B, for instance to merge them back into O.

There are several ways to solve the problem, depending on the situation. Let’s take a look.

Using a GUI #

For our first case, let’s assume A and B are on our development computer and we have a graphical session opened.

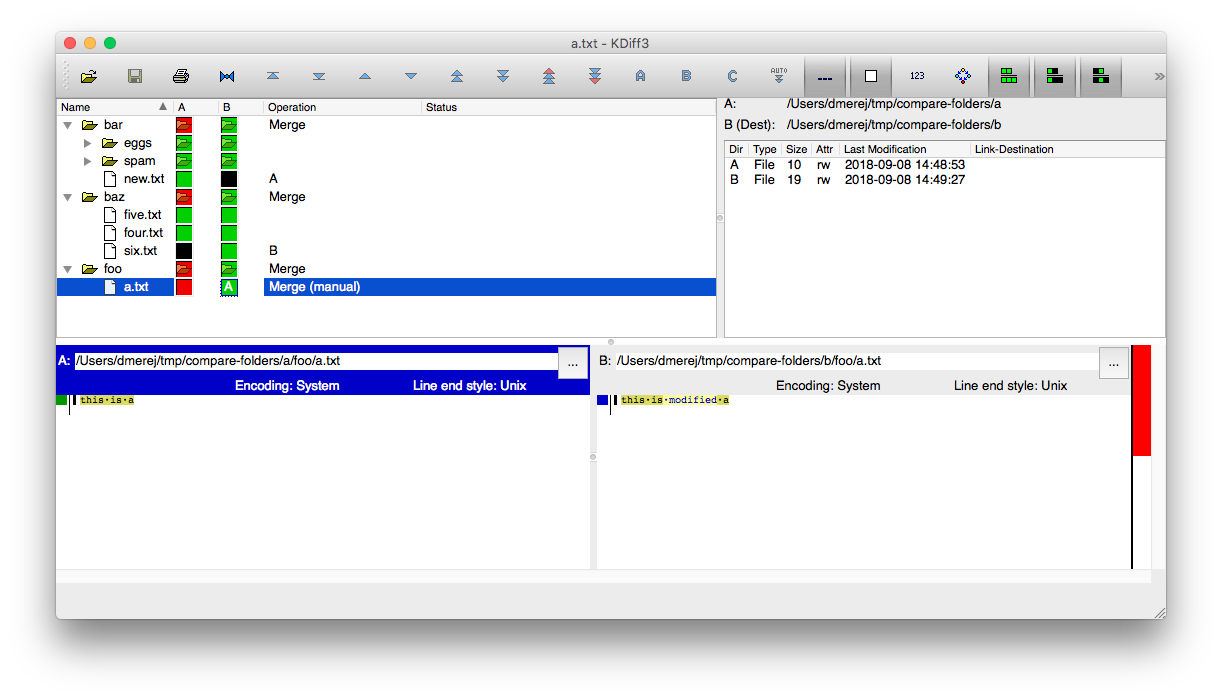

We can use many GUI tools for this task, here’s an example with Kdiff3:

On the top left pane we have an overview of all the differences between the A and B directories, and we can see that:

- The

bar/eggsandbar/spamdirectories are identical between A and B - There’s a new file named

bar/new.txtin A - There’s a new file named

baz/six.txtin B - The file

foo/a.txtwas changed both in A and B

On the bottom panes, since a.txt is selected, we can see the differences in the contents.

Using the command line #

Now let’s assume A and B are both on a remote server running Linux1 and we can’t open a remote graphical session there.

What are our options?

Well, we could use a coreutils command.

Coreutils is a package which is both very old and present in almost any Linux operating system. It contains a collection of useful, small command line programs. Even when it is not installed, an other package (like busybox) is usually here to provide similar functionality.

Anyway, there is a coreutils command named diff we can use for the task at hand:

$ diff --recursive a b

Only in a/bar: new.txt

Only in b/baz: six.txt

diff --recursive a/foo/a.txt b/foo/a.txt

1c1

< this is a

---

> this is modified a

Boom! All the info we need.

diff offers lots of ways to tweak its behavior2. For instance, we can get more succinct info with the --brief option:

$ diff --recursive --brief a b

Only in a/bar: new.txt

Only in b/baz: six.txt

Files a/foo/a.txt and b/foo/a.txt differ

By the way, if git is installed on the remote server, we can also use it, with nice options like --stat or --word-diff3:

$ git diff --stat a b

a/bar/new.txt => /dev/null | 1 -

/dev/null => b/baz/six.txt | 1 +

{a => b}/foo/a.txt | 2 +-

3 files changed, 2 insertions(+), 2 deletions(-)

Remote directories #

Now let’s assume A and B are on two different remote servers: let’s call them abbot and costello respectively.

Also, let’s assume A and B contains lots of big files, so we cannot copy the A directory from abbot to costello and use the previous technique. We can, however, transfer small files between the two servers. Here’s we can do.

First, we log in to abbot:

ssh user@abbot

Then, we go inside the a directory:

cd a

Then we run the following command:

find . | sort > ~/manifest-a

Explanation:

find .lists all the files and directories inside the current working directory.- The order of the files returned by find are not deterministic and can change form one file system to another, so we use a pipe (

|) to take the output offindand pass it to thesortcommand. (sortis also part of the coreutils package). - Finally, we use an angle bracket (

>) to write the output ofsortto a file in the home directory: (~/manifest-a): we must not write the manifest-a file inside theadirectory, otherwise the manifest may contain itself!

Now, we do the same on costello:

ssh user@costello

cd b

find . -type f | sort > ~/manifest-b

Then we use scp to transfer the A manifest to costello:

# On abbot

scp manifest-a user@costello:

Now we have two text files on costello, both containing a list of all the files. So, we use diff on the manifest files themselves:

diff ~/manifest-*

...

-./bar/new.txt

...

...

+./bar/six.txt

That takes care of the contents of the directories. What about contents of the files themselves ?

Well, we can use another coreutils tools called shasum.

shasum can be used to compute a checksum of the contents of a given file. It will generate the same output if the contents are the same, and if two files are different, there’s almost zero chance their checksum will be equal. 4

We can call shasum with a list of files as arguments, like this:

shasum file1.txt file2.txt

Here we need to call shasum with the whole list of files, so we call find . again but with the -type f option to select only the files and ignore the directories. This gives us a list of lines, so we use xargs (also in coreutils) to convert them into a list of command line arguments5, and finally write the result in a a.shasum file:

find . -type f | xargs shasum > ~/a.shasum

Here are the contents of the a.shasum file:

791c4ba196e0faea35e0c5fbe46e64da bar/eggs/two.txt

23f4a2592b2e4dee0444983a6e53c23e bar/new.txt

...

Now we can transfer the a.shasum file to costello:

$ scp a.shasum user@costello:

Finally, we can use shasum again with the --check option: it will read each line, parsing the file name and expected checksum, then compute the actual checksum for the given file and check if it matches the expected value:

$ cd b

$ shasum --check ~/a.shasum

./bar/eggs/two.txt: OK

./bar/spam/one.txt: OK

...

./foo/a.txt: FAILED

...

shasum: WARNING: 1 of 5 computed checksums did NOT match

And we’re done: from the differences of the manifests we know which file are missing or were added, and from the list of checksums we know which files differ.

Conclusion #

We saw that we can use nothing but command line tools from the coreutils package to compare the contents of two directories: the technique we used was working exactly the same way several decades ago, and will probably continue to work for a long time.

So, if you liked the techniques show here, here’s my advice to you: next time you are confronted with a task similar to the one we just studied, take a look at all of the coreutils documentation and try using them. If you do this often, after a while you’ll have gained a nice addition to your skill set.

Oh, and if you think “this is all useless”, please read this enlightening paper called Command-line Tools can be 235x Faster than your Hadoop Cluster :)

Cheers!

-

I hear there are people running operating systems other than Linux on remote servers. I’m sorry if this is the case for you. ↩︎

-

If you’d like to see all of what

diffcan do, feel free to runman diffand be amazed! ↩︎ -

Git is smart enough to see that neither A and B are inside a directory it controls, and if A and B were inside a git working tree, you could use the

--no-indexoption, as explained in the documentation ↩︎ -

You may already have heard of md5 sum: it works exactly the same way but uses an older algorithm to compute the checksum and its usage is generally discouraged. ↩︎

-

If you use zsh you can also ask it to list all the files directly with a glob extension, like this:

shasum **/*(.) > ~/a.md5. Yeah zsh! ↩︎

Thanks for reading this far :)

I'd love to hear what you have to say, so please feel free to leave a comment below, or read the contact page for more ways to get in touch with me.

Note that to get notified when new articles are published, you can either:

- Subscribe to the RSS feed

- Follow me on Mastodon

- Follow me on dev.to (mosts of my posts are mirrored there)

- Or send me an email to subscribe to my newsletter

Cheers!