Is TDD Worth It?

Well, here is a good question! Here’s what I have to say:

- I don’t know

- It depends

Those are, by the way, two very valid answers you can give to any question. It’s OK to not have a universal answer to everything ;)

Still, I guess you want me to elaborate a tad more, so here goes …

My testing story #

I’ll start by describing my own experience with testing in general, and TDD more specifically. Hopefully it will help you understand how I came to the above answer. It’s a long story, so if you prefer, you can jump directly to the so what? section.

Shipping software #

The story begins during my first “real” job.

I was working in a team that had already written quite a few lines of

C++ code. We were using CMake and had several git repositories.

So I wrote a command-line tool in Python named qibuild1 that would:

- Allow developers to fetch all the git repositories into a common “workspace”

- Run

CMakewith the correct options to configure and build all the projects.

The idea was to abstract away the nasty details of cross-platform C++

compilation, so that developers could concentrate on how to implement the

algorithms and features they were thinking about, without having to care

about “low-level” details such as the build system.

The tool quickly became widely used by the members of the team, because the command line API was nice and easy to remember.

$ cd workspace

$ qibuild configure

$ qibuild make

$ qibuild install /path/to/dest

It also began to be used on the build farms, both for continuous integration and release scripts.

Soon, I had to add new features to the tool, but without breaking the workflow of my fellow developers.

I decided to advise my co-workers to not use the latest commit on the master

branch, as they did for the rest of the company’s source code,

and instead, I started to make frequent releases.

So instead of running git pull, they could just use: pip install -U qibuild

and get the latest stable release. 2

Testing was complicated: the code base was already quite large, and the safest way to make sure I did not break anything was to re-compile everything from scratch (that alone took something like 15 minutes), and then perform a few basic checks such as:

- Did the newly-compiled binaries run? 3

- Was incremental build working?

Making testing easier #

My first idea was to write a bunch a “example” code.

Instead of having to compile hundreds of source code files spread across several projects, I could use two projects with just two or three source files:

test

world

CMakeLists.txt

world.h

world.cpp

hello

CMakeLists.txt

main.cpp

The world project contained source code for a shared library,

(libworld.so), and the hello project contained source code for an

executable (hello-bin) that was using libworld.so.

Compiling world and hello from scratch just took a few seconds, so testing

manually was doable.

But I was not very good at testing manually. Quite often I forgot to test some corner cases, and so many bugs were introduced without me noticing.

So I decided to start writing automated tests.

First tests #

The tests looked like:

class ConfigureTestCase(QiBuilTestCase):

def setUp(self):

pass

def test_configure(self):

self.run(["qibuild", "configure", "hello"])

def test_build(self):

# We need to configure before we can build:

self.run(["qibuild", "configure", "hello"])

self.run(["qibuild", "build", "hello"])

def test_install(self):

# We need to configure and build before we can install:

self.run(["qibuild", "configure", "hello"])

self.run(["qibuild", "build", "hello"])

self.run(["qibuild", "install", "hello", self.test_dest])

# do something with self.test_dest

def tearDown(self):

# Clean the build directories:

super().clean_build()

# Clean the destination directory for install testing:

if os.path.exists(self.test_dest):

shutil.rmtree(self.test_dest)

Few things to note here:

- No asserts

- The code to run the

qibuildcommands and cleaning the build directories is in aQiBuilTestCasebase class - If something goes wrong, it’s hard to know exactly why because we don’t know which build directories are “fresh”

- It’s not clear where the installed files go …

- Tests are slow because

helloandworldget compiled a lot of times.

At the time, that’s all the tests I had.

That meant I could do refactoring without fearing regressions to much, but I still had to run the entire test suite to be a little more confident about any change I just made.

I also started measuring test coverage 4 and was unhappy with the results. (60% if I recall correctly)

I also noticed that even though I was very careful, every release I made had some serious regressions, and so members of my team started to get reluctant to the idea of upgrading.

Code was clearly becoming cleaner, but this was not a good enough reason for them to upgrade.

The Light At The End of the Tunnel #

The decision to try TDD came from several sources, I’m not sure which was the decisive one at moment, but here are a few of them:

- Robert Martin: What Killed Smalltalk Could Kill Ruby, Too

- Destroy All Software: “classic” seasons 1 to 5.

- Boundaries, by Gary Bernhardt

So there, I started using TDD for all the new developments, and I kept doing that for several years.

Coverage went up, tests became more reliable and useful 5, regressions became more and more uncommon, adding new features became simpler and easier, and overall everyone was happy with the tool.

For the curious, here what the tests looked like: 6

def test_running_after_install(qibuild_action, tmpdir):

qibuild_action.add_test_project("world")

qibuild_action.add_test_project("hello")

qibuild_action("configure", "hello")

qibuild_action("make", "hello")

qibuild_action("install", "hello", tmpdir)

hello = qibuild.find.find_bin(tmpdir, "hello")

subprocess.run([hello])

Turning into a TDD zealot #

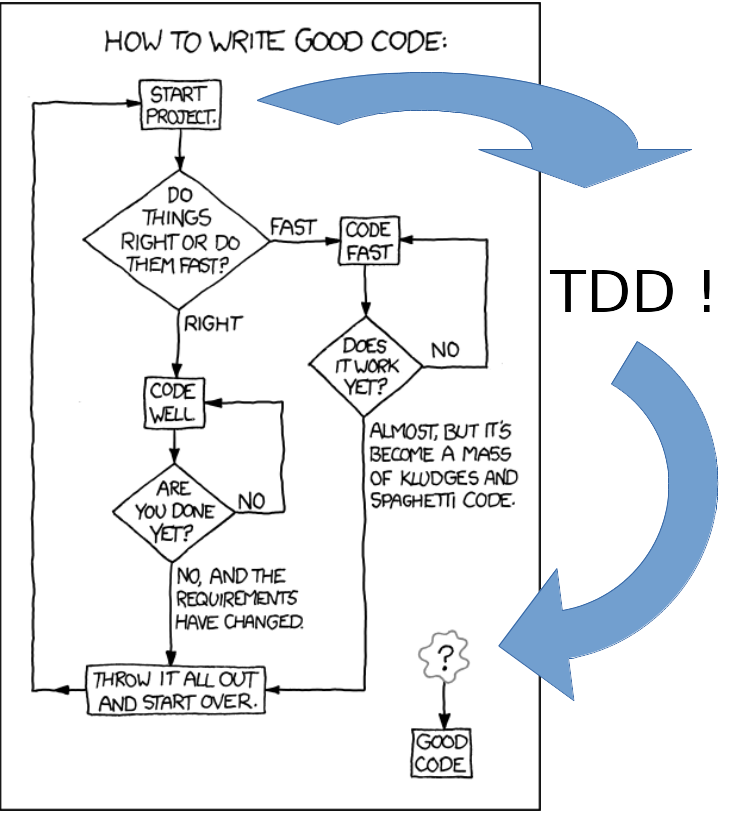

So, now I had finally solved that xkcd puzzle: 7

All I had to do was to write tests first, and everything would be OK!

But no-one around me believed me.

A few of them tried, but they gave up soon.

Many of them were working with “legacy” code and just making sure the old tests still pass was challenging enough.

I tried to told them about the classical beginners mistakes but it did not work.

But I was right! I had seen the light! It did not matter if I did not manage to convince anyone, I was right, and they were wrong.

The expert beginner #

I began realizing how little I knew about testing thanks to this very blog.

You can read more about this in “My Thoughts on: ‘Why Most Unit Testing is Waste’”.

It was then I understood that maybe things were not that simple.

I wrote two more articles to remember myself that my thoughts on testing were not completely black and white: 8

Realizing the truth #

This happened after I took a new job in an other company.

People there were ready to try TDD, and I was lucky enough to be there when two new projects started.

- One of them was some

C++code to read and write large encrypted files. - The other was a small piece of server written in

Go.

Surely this time, people willing to try would have no excuse (no legacy code this time!), and I even gave a talk to the whole team about TDD 9

But nope, it did not go as I expected:

-

For the

C++part, they used TDD until they started working on a small binary, that would encrypt and decrypt files from the command line. “We’ll use the binary during QA, surely we don’t need to use TDD just to write source code of the binary.”, they say. “Plus, we already have tests where we mock theEncryptorclass, no need to write and run the same tests with the ‘real’ encryptor class, bugs will be caught during QA anyway”. -

And in

Go, they wrote a few tests, but not that much, and many issues were caught by the compiler and the various linters they used anyway.10

Maybe TDD was working for me just because:

- It suits the way my brain work. I have a hard time doing several tasks at once, and the whole idea of the ‘red’, ‘green’, ‘refactor’ cycle helps me focusing on just the right stuff at the right time.

- I suck at doing tests manually.

- I produce a lot of typos.

- I used a language where tests are required to find problems. (The type system and the linters can only catch so much when you’re using a “dynamic” language such as Python)

- I had a very good test framework, and writing clean test code was easy after the 3rd refactoring or so :)

Applying TDD for a web application #

One day, I wondered how hard it would be to implement a wiki from scratch.

The basic stuff seemed easy enough:

- The server knows how to map the

/fooURL and afoo.htmlfile written on disk. - When a user visits

/foo/edit, he gets a form where he can type some Markdown code. - Then, when he clicks the

submitbutton, bothfoo.mdandfoo.htmlare generated.

Compiling #

I decided to write the server in Go.

This was new to me, because it was the first time I was working with a language with such a short compilation time.

Creating the loop #

I found myself forgetting to type go build before restarting the server, so I

wrote this short script:

# dev.py

print(":: Starting loop")

print("> Will stop as soon as the build fails")

print("> To restart the server, press CTRL-C")

while True:

cmd = ["go", "build", "server.go"]

subprocess.check_call(cmd)

try:

cmd = ["./server"]

subprocess.check_call(cmd)

except KeyboardInterrupt:

pass

Here’s how the script works, assuming the dev.py script is running

and you are in a state where the server is running with the latest version of

the source code:

- You write some

Gocode - You press

CTRL-C:- If the code compiles, the server is restarted with the latest changes

- If not, the script crashes, and you have to fix the build before re-running it.

Most of the time (especially when you get better at mastering the Go

language), you get the new version of code running very shortly after

saving the .go source file you were working on. 11

Testing #

After a while, I started having the server generating HTML forms, and I

found myself filling the same form and hitting the submit button over and

over again.

So I started automating, using py.test and selenium

First, I wrote a fixture so that the server source code will always get built before running:

@pytest.fixture(autouse=True, scope="session")

def build_and_run():

subprocess.check_call(["go", "build"])

process = subprocess.Popen(["./server"])

yield process

process.kill()

Then I wrote my own browser fixture, using the “facade” design pattern to

hide the selenium API:

class Browser():

def __init__(self):

self._driver = webdriver.Chrome()

def click_button(self, button_id):

button = self._driver.find_element_by_id(button_id)

button.click()

def read(self, path):

full_url = "http://localhost:1234/%s" % path

self._driver.get(full_url)

return self._driver.page_source

This allowed me to write things like this:

def test_edit_foo(browser):

browser.read("/foo/edit")

browser.fill_text("input-area", "Hello, world")

browser.click_button("submit-button")

assert "Hello, world" in browser.read("/foo")

That turned out to be a very nice experience.

I could:

- Insert a breakpoint using

pdb - Start the test I wanted with

pytest -k edit_foo - And when the code was paused, interact with the browser and experiment in

Python’s REPL to write the rest of the tests and the assertions, without first

learning the entire

seleniumAPI by heart.

Then again, the feedback loop was very short. I could edit the HTML to add

the proper id attribute, and then re-run the tests to check if the generated

HTML looked good in a web browser.

So, was I writing tests before or after? And did it matter?

Writing Software #

Around the same time, I watched Writing Software, a talk David Heinemeier Hansson gave in RailsConf 2014 Keynote.

You can watch the talk on youtube.

In it, David talks about TDD, but it’s only a small fraction of his talk, and I highly recommend you listen all it has to say and not focus on the most controversial parts.

Anyway, the talk gave me a lot to think about.

So what? #

For me, TDD worked really well for several years for one of the projects I’ve been working on.

I liked the fast feedback loop, the fact I could refactor with confidence thanks to well-written and fast tests, and how I could just type one command and have an answer to the eternal question: “Did I just break something?”.

But, when I started working on a Web application written in Go,

it turned out I could get the same feeling and the same kind of loop

without doing TDD at all. All it took was a

10 lines Python script.

The ‘what’, the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ #

To say it differently, I think I was too obsessed with the what and the how and forgot about the why, something I feel happens far too often when it comes to new technologies.

Let me explain:

For me, the what of TDD is just one sentence: “Write your tests firsts, before the production code”.

The how is: “Follow the rules: it’s red, green, refactor”.

Those are very easy to remember and explain, but I think I did not manage to convince anyone to try because they did not really care about the what and the how. They wanted to know why.

I kept telling them they should always write their tests first, that they should try and stick to it for several weeks before “getting” it, TDD not being something you could “learn in one week-end”.

But that’s not what they wanted to hear, they wanted to know why TDD was worth trying, and the answer: “Because it worked really well for me and my project” was not good enough.

So here goes: why do we do TDD?

I think TDD is just a framework. It’s a set of tools, rules and conventions you can use to write better tests and better production code.

But what are “good tests” and “good production code”?

-

Good tests are tests that read like a well-written specification. When they fail, they give you a lot of details and clues about the location of the bug in your production code.

-

Good production code is code that is easy to read and is not your first draft. As a software writer, it’s the result of many iterations so that your fellow team mates can read and modify it with confidence. It’s code that is easy to change.

So, write your tests first, write them last, or don’t write any, but please remember what really matters: your code will be written once, and read many times.

Also, you are not paid to write code. What matters is that the features that need to be implemented are done and that the bugs are fixed.

Thanks for reading!

-

That’s where I realized how important changelogs were. ↩︎

-

It’s not that obvious when your binaries are built for Linux, macOS and Windows, and there are

.so,.dyliband.dllfiles involved. ↩︎ -

At the time, I thought it was a good idea to measure test coverage.

I’m not so sure anymore. ↩︎ -

By that I mean that I started having just a few tests failures that pointed me directly to the bug I just introduced. ↩︎

-

Fifty shades of testing? ↩︎

-

I used stuff I learned from Uncle Bob’s videos on the subject ↩︎

-

We use gometalinter by the way. ↩︎

-

You may wonder how I managed to write the contents of the

dev.pyfile itself. Short answer: I usedCTRL-\, which makes Python exit with a core dump and effectively exit thewhile Trueloop even though the code compiles. ↩︎

Thanks for reading this far :)

I'd love to hear what you have to say, so please feel free to leave a comment below, or read the contact page for more ways to get in touch with me.

Note that to get notified when new articles are published, you can either:

- Subscribe to the RSS feed

- Follow me on Mastodon

- Follow me on dev.to (mosts of my posts are mirrored there)

- Or send me an email to subscribe to my newsletter

Cheers!