My JavaScript Workflow

Following the (relative) success of How I lint My Python, today I’d like to talk about the tools and techniques I use while writing JavaScript at work.

The cycle #

Regular readers of this blog won’t be surprised by the fact I’m using TDD and thus that I already have a “red”, “green”, “refactor” cycle.

What I like about TDD is that each of the phases has a very precise goal and a specific way of thinking about the code:

- red: think about API and architecture: what the production code would look like

- green: just get the tests to pass, write the feature as quickly and as simply as possible

- refactor: consider the mess you’ve made, and clean it up.

My cycle when developing JavaScript encapsulates this workflow:

- Select a feature or a bug fix to implement

- Write tests or production code

- Run the tests

- Back to step 2 until I’m done with the feature or bug

- Add

flowannotations - Rewrite history

- Create merge request

- Go back to step 6 if required

- Tell GitLab to merge the changes when the CI passes

flow annotations after the whole TDD cycle. This is probably because I’m used to work with dynamically typed languages, so I’m still not used to static typing. Thus, I deal with types in a separate phase. If you come to “flowed” JavaScript from a C++ background, you may prefer adding types first. I’ve also found that, when you don’t have any tests, flow can be of great help during refactoring.

Anyway, let’s go through these steps one by one. You will see how the tools I use are tailored for each specific task.

Writing code #

We use eslint to check coding style violations or problematic patterns of code.

For instance:

import foo from 'barr';

function baz() {

let bar = 42;

if(bar) {

// ...

}

}

$ eslint foo.js

src/foo.js

1:17 error Unable to resolve path to module 'barr'

4:7 error 'bar' is never reassigned. Use 'const' instead

5:3 error Expected space(s) after "if"

I want to know immediately when I’ve mistyped an import or a variable name, and eslint helps catching a lot of errors like this.

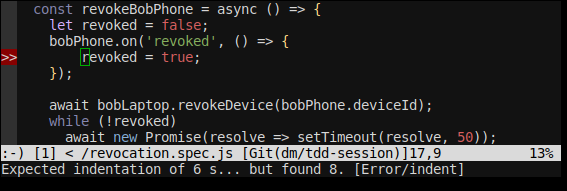

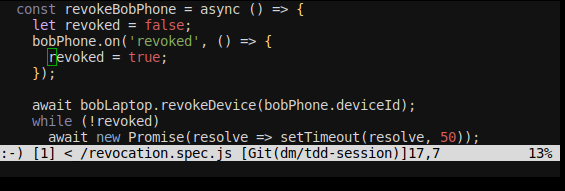

So, I’m using vim-ale inside neovim to have eslint run as soon as I save.

(I could make it run continuously, but I find it too distracting).

I use the gutter so that as soon as it’s gone I know all lint errors are fixed, as shown on these screenshots:

With the gutter:

Without:

Running the tests #

For the tests we use mocha and chai.

Here’s what the tests look like 1:

// In Tanker.js

describe('Tanker', () => {

it('can be instanciated', () => {

...

}

it('can be opened', () => {

...

}

}

// In revocation.js

describe('revocation', () => {

let bob;

let bobLaptop;

let bobPhone;

function revokeBobPhone() {

bob = helper.makeUser('Bob');

bobLaptop = bob.makeDevice('laptop');

bobPhone = bob.makeDevice('phone');

bobLaptop.revokeDevice(bobPhone);

}

specify('revoking a device', () => {

revokeBobPhone();

expectWiped(bobPhone);

});

specify('can access encrypted resources even with a revoked device', () => {

const message = 'now you see me';

const encrypted = bobLaptop.encrypt(message);

revokeBobPhone();

const clear = bobLaptop.decrypt(message);

expect(clear).to.eq(message);

});

specify('Alice can share with Bob who has a revoked device', () => {

const alice = helper.makeUser('alice');

const alicePhone = alice.makeDevice('phone');

revokeBobPhone();

const message = 'I love you';

const encrypted = alicePhone.encrypt(message, { shareWith: [bob.userId] });

const clear = bobLaptop.decrypt(encrypted);

expect(clear).to.eq(message)

expectFailWith(bobPhone.decrypt(encrypted), /Device is revoked/);

});

});

The whole test suite takes a few minutes to run (we have a pretty big suite of integration tests).

In order to keep the TDD cycle short, and assuming I’m working on something related to the revocation, I’ll start by adding a .only after the describe, like this:

describe.only('revocation', () => {

...

});

and then I’ll run mocha in “watch” mode:

$ yarn test:tanker --watch

So, as soon as I save the production or the test code, the tests I’m interested in will run.

The nice thing is that we have a eslint rule that prevents us to ever merge code that contains a call to .only, so as long as there’s a gutter in the tests files I know I have to remove the .only and run the whole test suite.

Running flow #

We also use flow and type annotations to check for a whole bunch of errors during static analysis (which means checks that are done without the code running):

import { fromBase64 } from './utils';

type OpenOptions = {

userId: string,

secret: string,

...

};

export class Tanker {

userId: Uint8Array,

userSecret: Uint8Array,

open(userId: string, userSecret: string) {

...

}

}

You may be wondering why the user secret is a Uint8Array inside the Tanker class, but a base 64 string in the OpenOptions.

The reason is that almost all cryptographic operations need Uint8Array, but as a convenience for the users of our SDK we let them use base 64 encoded strings.

Thus, if you pass an incorrect type:

import { randomBytes } from './utils';

import { createUserSecret } from './tanker';

const userId = randomBytes(32);

const secret = createUserSecret(userId);

tanker.open(userId, secret);

flow will warn with a message like this:

597: const tanker = new Tanker( { url: 42 });

^^^^^^^^^^^ object literal. This type is incompatible with the expected param type of

84: constructor(options: TankerOptions) {

^^^^^^^^^^^^^ object type

Property `url` is incompatible:

597: const tanker = new Tanker( { url: 42 });

^^ number. This type is incompatible with

36: url: string,

^^^^^^ string

Found 7 errors

As you can see the message spawns on several lines, and you often need all the information flow gives you to understand what’s wrong.

Thus, it’s not very practical to have it run as a vim-ale linter (although it’s doable).

Also note I want to run flow not as often as the tests or eslint. It takes quite a while to think about the correct annotation to use, and it’s a completely different mind process than writing new tests, refactoring code or implementing features.

So, with that in mind, here’s the solution I’ve found.

First, I open an other terminal to run this simple script:

import subprocess

import neovim

def main():

nvim = neovim.attach("socket", path="/tmp/neovim")

nvim.subscribe("refresh")

try:

while True:

_ = nvim.next_message()

subprocess.run(["yarn", "flow"])

except:

pass

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

What it does is subscribe to a Neovim event named ‘refresh’, and run yarn flow every time it is emitted.

From Neovim, all what’s left is to run:

:nnoremap <cr> :wa\|call rpcnotify(0, "refresh")<cr>

Let’s break this command into parts:

nnoremap <cr>: tells Neovim we want to map the pressing of ‘Enter’ in normal mode to a new chain of commands.- The first command is

:wa(write all). - The second command (separated with an escaped pipe,

\|), is calling therpcnotifyfunction which will trigger therefreshevent. - Finally, we end the chain of commands with

<cr>so that there’s no need to press ‘Enter’ a second time.

And so, all I have to do when I’m pondering how to use types properly is to go to normal mode, press enter, look at the end of the flow output and check if the number of errors is decreasing.

If I get an error I don’t understand, I can scroll up a little bit to get the full message associated with this error.

Rewrite history #

Making the git commit #

Once all the tests pass and flow no longer find errors, it’s time to make a git commit.

For this, I’m using git gui. It’s ugly but:

- It works well on every platform and comes bundled with git

- You can select things to add or remove to the current commit with the mouse, by chunks or by line

- It has a spell checker for the commit message

- You can create your own actions in the menu (personally I use

cleana lot).

I also like the fact it does not have syntax highlighting. It gives me an opportunity to look at my code in a new way, which allows me to spot mistakes I would have missed if I only looked at them from the editor.

Note: adding custom actions is done in ~/.config/git/config:

[guitool "clean"]

cmd = git clean -fd

confirm = true

Rebasing #

I also almost always rebase my work on top of the master branch to make sure the history is as clean as possible. Re-ordering, squashing or splitting commits can often help reviewers.

For this I use my custom git alias and neovim (again) to edit the “rebase todo”

[alias]

ro = rebase -i origin/master

$ git ro

pick 6558885f less babel cruft

pick 8c2b1c3f FIXME: revocation tests to be written

pick 1b36450f fix revocation bug

Creating the merge request #

Finally it’s time to create a merge request. For this I use tsrc which is the tool we use to help us manage several git repositories and contains some nice features leveraging the GitLab API:

$ tsrc push -a theo

=> Running git push

...

=> Creating merge request

=> Assigning to Théo

:: See merge request at http://gitlab.dev/Tanker/SDK/merge_requests/431

Accepting the merge request #

Our GitLab configuration does not allow anyone to push directly to master, and prevent us from merging if the CI does not pass.

This ensures CI failures are dealt with the high priority they deserve.

But, since CI failures are rare, what we often do is just tell GitLab to merge the request as soon as CI passes, and of course we use tsrc for this:

$ tsrc push --accept

Conclusion #

And that’s all I have to say today.

I hope it gives you a sense of what it’s like to work with a bunch of small tools, all focused to do one task, and do it well.

This is also the long-version answer to “Why do you not use an IDE ?”. As I explained, I actually enjoy having to use different tools depending on the context, it greatly helps me focus on the task at hand.

Cheers!

Thanks for reading this far :)

I'd love to hear what you have to say, so please feel free to leave a comment below, or read the contact page for more ways to get in touch with me.

Note that to get notified when new articles are published, you can either:

- Subscribe to the RSS feed

- Follow me on Mastodon

- Follow me on dev.to (mosts of my posts are mirrored there)

- Or send me an email to subscribe to my newsletter

Cheers!